Guitar Scales Explained with Graphics and Clear Music Theory

Guitar Chalk is an online magazine committed to quality content for guitar players and musicians. You can access the original version of this article there via: https://www.guitarchalk.com/guitar-scale-theory-simple-explanation/

In all likelihood, you can play some guitar.

You may even be able to play a lot of seriously technical and fast lead segments that are rooted in some kind of scale.

However:

You don’t fully grasp or understand the concepts behind the notes and patterns you use. The scales you play are a mystery. There’s something in you that knows it would be easier if you understood guitar scale theory and music theory in general.

And it’s not that you want (or need) to know all music theory.

Rather, just enough to help give meaning to fretboard movement.

The right kind of music theory gives us a better understanding of the guitar scales we play and why we play them.

In my attempt to explain guitar scales, I’ll use enough theory to thoroughly discuss the concept while avoiding information that doesn’t benefit you directly in your understanding of the fretboard.

Supplemental Material for Learning Scales

For video lessons and more help with guitar scales, we recommended the Guitar Tricks courses. They’ll even let you try everything out free for 14 days. Afterwards you’ve still got 60 additional days to cancel with a full refund, no questions asked. You can check out my full review of Guitar Tricks here for more information or snag the free trial.

Knowing a Little Guitar Music Theory

For a long time, I didn’t know any theory.

I’ve always had a good ear but, didn’t really delve into theory until I started to realize that I was simply memorizing patterns without knowing how or why they sounded the way they did.

We’re doing ourselves a disservice if we don’t understand the basic theoretical concepts behind our guitar scales.

In this post, I’ll show you how to understand guitar scale theory in short paragraphs and plenty of pictures.

We’ll only cover what you need to know for guitar scales to make actual sense.

Let’s jump in.

Guitar Scale Theory Explained

The most basic explanation of a guitar scale would be the following:

A guitar scale is any sequence of musical notes ordered by frequency or pitch. | view large image

It’s less scary once you realize that, in its most basic form, a scale is little more than an ascending or descending sequence of notes. Pretty simple.

Further, scales are ordered by pitch.

Anssi Klapuri, in Signal Processing Methods for Music Transcription, defines pitch as the following:

Pitch is a perceptual attribute which allows the ordering of sounds on a frequency-related scale extending from low to high.

In other words, a scale is an ordered series of notes based on their frequency.

How do we break this down on the fretboard?

We start with basic intervals, whole and half steps.

Basic Intervals: Whole and Half Steps

We’ve already established that scales are a series of musical pitches. But, how are those pitches understood?

In music, pitch is indicated by the first seven letters of the alphabet:

A B C D E F G

Thus, each individual note (pitch) on the scale will have one of these letters associated with it.

Moving between these notes introduces you to the concept of changing pitch, which can be measured in half and whole steps.

Half Steps (semitones): If you start with your first finger on the 1st fret of the sixth string, then move your finger up to the 2nd fret on the same string, you’ve moved up in pitch one half step.

Whole Steps (wholetones): If you start with your first finger on the 1st fret of the sixth string, then move your finger up to the 3rd fret on the same string, you’ve moved up in pitch one whole step.

Example of a half step and whole step in a guitar scale diagram. | view large image

These terms give us a way to describe movement up and down the fretboard, particularly when we’re talking about ascending or descending scales.

Thus, scales can often be broken down into a mixed arrangement of half steps and whole steps, also called minor second and major second intervals.

Consider the following scale diagram:

Another example of a half step and a whole step in a guitar scale diagram.| view larger image

I’ve circled a half step and a whole step.

Whenever they show up in scales, they make up one and two fret jumps, respectively. If it’s a three fret jump, say the 1st to the 4th fret, we’d call that “one and a half steps,” or if it went from the 1st to the 5th fret we’d say “two whole steps.”

Alternatively, we can look at those longer fretboard distances in terms of intervals which go all the way up to 12 semitones or 12 frets.

You can refer to the following diagram for matching up intervals with fret distance from a given root note:

Scales and Keys

Key can be defined as the following:

The key is the root of the scale that a group of chords or notes fall into. For example, if you have three notes being played, let’s say they’re C, D and G, we know from the C major scale that this note sequence can be said to be in (or derived from) the key of C.

Thus, a key gives us a scale upon which a piece of music is based.

Let’s talk about this relationship.

What is the link between scales and keys?

We can know right away that our key is going to be one of the seven musical notes or pitches that we identified earlier (the letters). However, we need to keep in mind that scale notes are then taken directly out of that key. Thus, any piece of music is based off a scale, which has a key.

Were we to move the scale up or down the fretboard, the key would change.

Therefore the more correct explanation is that our songs have keys, which then indicate to us particular scales.

What’s the difference between scales, songs and keys? | view large image

Scales take their letter value from the root note or “tonic” of the scale sequence.

Once you know what scale you’re playing and in what key, you can move the scale or any segment of it to any location on the fretboard, thereby changing its key.

How to move scale shapes. | view large image

Chromatic Guitar Scales Explained

Western music uses 12 notes, which can be referred to as “The Complete Chromatic Scale.” On a keyboard or piano this is represented by seven white keys and five black keys.

On a guitar, it’s represented by 12 frets.

The chromatic scale on the guitar can be visualized by going from the open E on the sixth string to the 12th fret (high E) on the same string, at which point the pattern simply repeats.

Those 12 notes make up the complete chromatic scale on the guitar.

Chromatic scales are made up of a succession of semitones. | view larger image

In the above diagram we’ve only gone to the 10th fret to save space in the graphic but, the concept remains intact.

All the guitar scales you will ever see are derived from this simple 12-note system. Moreover, all the different sounds, melodies and arrangements we get come from a variation of this sequence.

It is made up of two types of notes:

- Naturals

- Accidentals

Naturals are notes that have only a letter value (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) and neither flats nor sharps attached to them. Accidentals have a letter value and either a sharp or flat associated with it, like B♭.

These make up all the musical notes in existence.

Delving into the A Minor Pentatonic Scale

Though the primary intention of this article is to cover the theory and technical aspects of guitar scales, we’ll delve into some basic application as well, using the A minor pentatonic scale as our example.

This scale is a fairly common pattern, particularly for guitar players.

We’ll cover the 10-fret model of the scale then break it down into smaller chunks. Keep in mind that any segment of the scale can, theoretically, be moved to any fret.

The A minor pentatonic scale from the first to the 10th fret. | view larger image

The small broken circles on certain dots signify the root notes at different octaves (which in this case is A).

What we want to do now is break the scale down into smaller, more usable segments, which can then be memorized and transposed anywhere on the fretboard.

We’ll start with the first few frets.

First Segment

The first segment of the scale falls within the first three frets and the first four strings of the guitar. This scale should be handled in three different steps during practice:

- Memorize the pattern as it is

- Memorize the sound

- Transpose the scale to another fret

Let’s say, for example, that you wanted to move the pattern up to the 5th fret. The tab would look like this:

You’re still jumping up one and a half steps for the two lower strings and one whole step for the two higher strings. However, the scale takes on a new key as a result of moving frets. Another way to say this is that you “transposed” the scale shape.

The key of the scale starting at the 5th fret is now D.

Second Segment

Since we’ve already covered the process of transposing to another fret, I won’t rehash that here. However, the same practicing goals apply.

Third Segment

The process repeats for the third segment.

10 Blues Scales that will Improve Soloing Technique

To expand on what we’ve already covered, I’ve found the bluesy-sounding scales listed below to be particularly useful in the following musical disciplines:

- Blues guitar playing styles

- Heavy rock chord progressions

- Modern pop and rock

- Western music’s dominant intervals and progressions

Most of today’s guitarists make their living in one of these areas or a subset thereof.

What to Think About

Use the diagrams first then start working through each mode without looking at the charts or as you’re able to commit them to memory.

If you need a process to follow, here’s what I would recommend:

- Play through the scale several times while looking at the diagram.

- Memorize the pattern by hand.

- Play through the scale several times again without looking at the diagram.

- Once you’ve begun to recognize the sound and associate it with the name of the scale, move onto the next pattern.

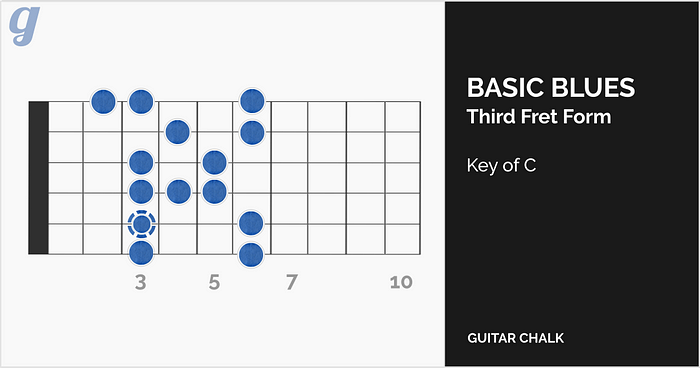

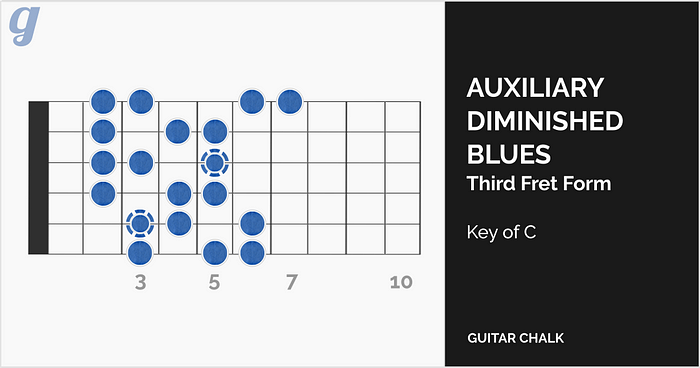

All scales are in the key of C at the third fret position.

1. Basic Blues

2. Major Blues

3. Pentatonic Minor

4. Blues Variation 1

5. Dominant Pentatonic

6. Auxiliary Diminished Blues

7. Dorian

8. Pentatonic Major

9. Pentatonic Neutral

10. Melodic Minor

Goals and Following Up

To really get to know these guitar scales you need to put in some time.

How much time will depend on your own practice schedule and your willingness to focus on the same material indefinitely.

Here’s a possible way of scheduling practice sessions for each of these scales:

- Monday: Basic Blues, Major Blues (30 minutes each)

- Tuesday: Pentatonic Minor, Blues Variation I (30 minutes each)

- Wednesday: Dominant Pentatonic, Auxiliary Diminished Blues (30 minutes each)

- Thursday: Dorian, Pentatonic Major (30 minutes each)

- Friday: Pentatonic Neutral, Melodic Minor (30 minutes each)

A good goal would be to stick with this schedule for four weeks (roughly a month).

By that time each scale will have been given two hours of intentional practice and focus, at which point you should be more than ready to move on to some application of those scales.

Here are a few articles I’d refer you to for some help with applying this knowledge:

- Basic Guitar Music Theory

- Arpeggios on the Higher Register

- 55 Guitar Finger Exercises

- The Total Intervals Guide

Conclusion

Understanding the musical concepts surrounding the guitar is tricky, since in-depth, complex music theory isn’t required to be a good guitarist. Yet, we need to know enough to know why we play what we play and what all the movement on the fretboard actually means.

Guitar scale theory is a good place to start and if you have a general knowledge about how scales work, you’ll be able to apply that knowledge to almost all other areas of your playing.

For more lessons that focus on theory and technique, checkout our online guitar lessons archive.

If you have questions or comments, get in touch with us via Twitter or the comments section here on Medium. Thanks for reading.

Flickr Commons Image Courtesy of Kmeron